Melatonin For Jet Lag: The Science Of Resetting Your Internal Clock

Crossing several time zones in a single flight is a modern kind of disorientation. Your body insists it is midnight while the sun pours through the hotel window, or it keeps you alert long after the local day has ended. Many travelers turn to melatonin for jet lag as a gentler way to realign their sleep without heavy sedatives.

At its core, melatonin for jet lag works because it speaks the same language as your internal clock. Understanding the science behind that clock—how it senses light, time, and rhythm—helps you use this hormone with intention rather than guesswork.

"Think of melatonin less as a sleeping pill and more as a timing signal for your brain." — Common guidance from sleep clinicians

Understanding Jet Lag And Your Internal Clock

Jet lag is not simply “being tired after a long flight.” It is a temporary mismatch between:

-

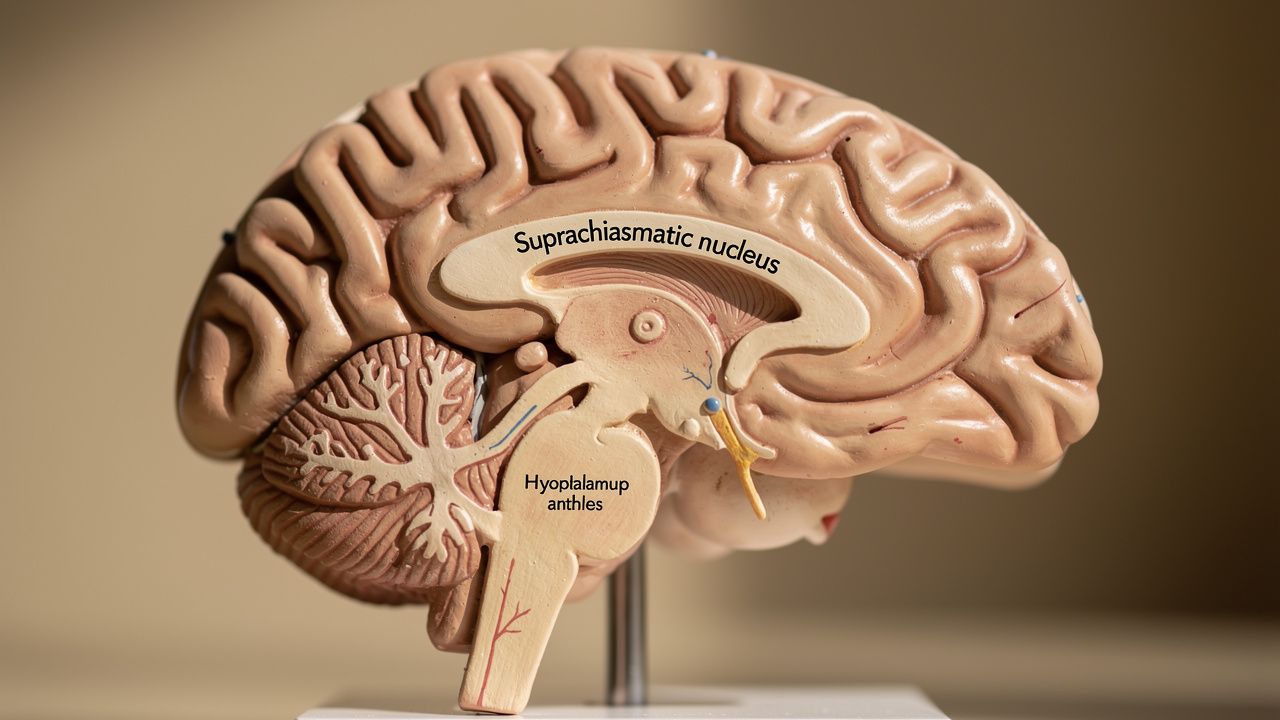

Your internal circadian clock (centered in the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN), and

-

The new light–dark cycle at your destination.

When those rhythms fall out of step, many people notice:

-

Trouble falling asleep or waking too early

-

Fragmented sleep with frequent awakenings

-

Daytime fatigue and sleepiness

-

Irritability, low mood, or loss of mental sharpness

-

Gastrointestinal upset and changes in appetite

The further you travel, the more intense this mismatch tends to be. Eastbound flights are usually harder because your body must advance its clock—shortening the day—while westbound travel asks the clock to delay, which the human body tolerates a bit more easily.

Melatonin for jet lag helps because melatonin is one of the body’s main time signals. When used thoughtfully, it can nudge that internal clock toward the local time at your destination.

"Sleep is the single most effective thing we can do to reset our brain health each day." — Matthew Walker, PhD, author of Why We Sleep

How Melatonin Works In The Body

Melatonin is often called the hormone of darkness, though research shows melatonin: beyond circadian regulation extends to immune function, antioxidant activity, and other physiological processes throughout the body. The pineal gland releases it in response to nightfall, and that nightly rise quietly tells your organs, “Night has begun; it is time to slow down.”

From Light To Hormone: The Nighttime Signal

The process begins in the eyes:

-

Light hits specialized cells in the retina.

-

These cells send signals to the SCN—the master clock in the hypothalamus.

-

As daylight fades, the SCN signals the pineal gland to start producing melatonin.

-

Melatonin levels rise about two to three hours before your usual bedtime, nudging body temperature down and reducing alertness.

If you sit in bright light late into the evening—especially blue light from screens—that signal is delayed. Melatonin production drops, and sleep comes later. Over time, this can shift or fragment your entire sleep–wake pattern.

For a deeper dive into this biology, SLP1’s overview of the science of circadian rhythms traces how light, neural pathways, and hormones form one continuous timing system.

A few quick facts about natural melatonin:

-

It rises in the evening, peaks in the middle of the night, and falls toward morning.

-

It does not directly control sleep, but it tells the body when night has started.

-

Its timing is tightly linked to light exposure and the regularity of your sleep schedule.

Supplemental Melatonin: A Time Cue You Can Choose

Supplemental melatonin is synthetic melatonin taken by mouth or other routes. It does not “force” sleep the way a sedative does. Instead, it acts as an extra time cue:

-

When taken in the evening, it tells the SCN, “Night is starting earlier now,” helping to advance the clock.

-

When taken at specific morning times, it can delay the clock, though this strategy is used more cautiously.

For many people, a short, planned course of melatonin—sometimes supported by products such as SLP1’s get to sleep—makes it easier to fall asleep and stay asleep on a new schedule without relying on stronger medications.

Over days, the brain begins to shift its own internal rhythms, and the supplement can usually be tapered off. Because the half-life of most oral melatonin is relatively short (around 30–60 minutes), its effect is more about when it is taken than how long it stays in the body.

Why Melatonin For Jet Lag Works: Mechanisms And Research

To understand why melatonin for jet lag is so helpful, it helps to picture your circadian clock as a 24‑hour loop that can be moved earlier or later. Melatonin changes when on that loop your body believes night has begun.

Phase Shifts: Moving Your Internal Night

Scientists describe these changes as phase shifts:

-

Phase advance (earlier clock):

Helpful for eastbound travel. Taking melatonin in the local evening strengthens the signal that “night has arrived,” so you feel sleepy closer to the new bedtime. -

Phase delay (later clock):

Sometimes used for westbound travel. In certain protocols, melatonin taken at carefully chosen morning times can delay the clock, although many travelers find they can manage westbound trips with light exposure alone.

Melatonin does two things at once:

-

Directly shifts the clock by acting on melatonin receptors in the SCN.

-

Indirectly supports the shift by helping you fall asleep when you otherwise would be awake, which reduces exposure to disruptive light at the wrong time.

Over several days, these small shifts accumulate, bringing your internal night into better alignment with local night.

What Clinical Trials Tell Us

The effectiveness of melatonin for jet lag has been studied in multiple randomized controlled trials and summarized in high-quality reviews:

-

Across ten trials, eight found that melatonin clearly reduced overall jet lag symptoms for flights crossing five or more time zones.

-

A Cochrane review estimated that for every two travelers who took melatonin, one experienced substantial relief compared to placebo (a strong effect size).

-

In one analysis, about 67% of placebo users reported severe jet lag after an eastbound flight, compared with only 17% of melatonin users.

-

On a 0–100 jet lag severity scale, melatonin improved scores by roughly 17–20 points for both eastward and westward flights.

-

People taking melatonin fell asleep faster, slept more soundly, and reported better daytime energy and mood.

Summaries of this work, including timing diagrams and circadian explanations, appear in resources such as SLP1’s discussion of the science of sleep regulation.

These findings align with the design of targeted formulations—like get to sleep—that aim to shorten sleep onset and improve sleep quality when your body clock is out of sync.

"Strategic use of light, darkness, and melatonin can meaningfully reduce jet lag for many travelers." — Adapted from guidance by major sleep medicine organizations

Dosing Melatonin For Jet Lag: How Much, Which Form, And Quality

When using melatonin for jet lag, more is not always better. The dose, the speed of release, and the quality of the product all influence how well it works.

How Much Melatonin To Take

Research suggests that doses between 0.5 mg and 5 mg are generally effective for shifting the clock and easing jet lag:

|

Dose (mg) |

Main Effect |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

0.5 mg |

Shifts circadian timing |

Often as effective as higher doses for clock adjustment |

|

2–3 mg |

Clock shift + noticeable sleepiness |

Common starting range for many adults |

|

5 mg |

Stronger sleep-promoting effect |

People may fall asleep faster; no clear added jet lag benefit vs 0.5 mg |

|

>5 mg |

No proven extra benefit for jet lag |

May raise risk of grogginess or side effects |

General guidance for healthy adults:

-

Start at the lower end of the range (e.g., 1–3 mg).

-

Take it 30–60 minutes before your target bedtime at the destination.

-

Use it for a few nights rather than indefinitely.

-

Avoid stacking melatonin with other sedative medications without medical advice.

Because melatonin is a hormone and individual responses vary, it is wise to discuss dosing with a healthcare professional—especially if you take other medications or have chronic health conditions.

Fast-Release, Slow-Release, And Nasal Spray

For jet lag, timing is everything. Studies comparing formulations show:

-

Fast-release melatonin (tablets or capsules) tends to work best. It creates a short, clear nighttime signal that helps the circadian clock adjust.

-

Slow-release melatonin spreads the dose over many hours. In one study, a 2 mg slow-release tablet was less effective for jet lag than smaller fast-release doses. Extended release can also linger into daytime, causing grogginess.

-

Nasal sprays are a newer option. By absorbing through the nasal mucosa, they reach the bloodstream quickly, which may be appealing when you want a rapid onset of sleep after landing. SLP1’s comprehensive guide to melatonin nasal spray explores how this route compares with oral forms in terms of onset, convenience, and travel use.

Because in the US melatonin is sold as a dietary supplement rather than a prescription drug, quality control varies:

-

Independent testing has found some products to contain far less—or far more—melatonin than the label claims.

-

A few supplements were even contaminated with other substances, such as serotonin.

To reduce these risks, choose a reputable brand, favor a melatonin‑only product (without unnecessary added herbs), and consider sticking to well-established formulations such as fast-release tablets or sprays that clearly list their contents.

Timing Melatonin For Jet Lag: Eastbound And Westbound Flights

When you take melatonin for jet lag often matters more than the exact dose. Taken at the right time, it helps your clock align with local time; at the wrong time, it can delay your adjustment or make you sleepy when you need to be awake.

General Timing Principles

A few broad rules help most travelers:

-

Take melatonin close to your target local bedtime—typically between 10 p.m. and midnight at your destination.

-

Swallow it about 30–60 minutes before you plan to sleep.

-

For many routes, starting on the evening of arrival and continuing for two to five nights is enough. Preflight dosing usually adds little benefit and complicates timing.

Apps, tables, and schedules based on the science of circadian timing can refine these general rules based on your route and chronotype. If you use a product like get to sleep, set a consistent reminder so you take it at the same local time each evening while your body is adjusting.

Example Plan For Eastward Travel

Imagine flying from New York to Paris (six time zones east), arriving in the morning.

On the flight:

-

Sleep if you can during the second half of the flight.

-

Avoid bright screens and overhead lights during hours that correspond to the destination’s night.

Day of arrival:

-

Get bright natural light in the late morning and early afternoon.

-

Avoid long naps; if needed, take a short nap (20–30 minutes) before midafternoon.

First three nights:

-

Take melatonin for jet lag 30–60 minutes before your target Paris bedtime (for many, between 10 p.m. and midnight local time).

-

Keep lights dim in the evening; avoid screens for an hour before bed.

-

Repeat for 2–5 nights, then reassess your sleep.

This pattern helps advance your internal clock so that your brain starts treating the earlier local night as “true night.”

Example Plan For Westward Travel

Now imagine flying from Paris back to New York (six time zones west), arriving in the afternoon.

Day of arrival:

-

Seek bright light in the late afternoon and early evening to encourage your clock to shift later.

-

Try to stay awake until a reasonable local bedtime.

First nights:

-

Many people can adjust to westbound travel with light cues alone, since lengthening the day feels slightly more natural to the circadian system.

-

If you choose to use melatonin for jet lag, a modest dose near your new local bedtime may help you fall asleep and stay asleep through early morning awakenings.

Some protocols suggest using morning melatonin to delay the clock, but this can cause significant daytime drowsiness if not timed precisely. Discuss this approach with a clinician if you are considering it, especially for complex itineraries.

Safety, Side Effects, And Who Should Avoid Melatonin For Jet Lag

For healthy adults using melatonin for jet lag over a few days, studies suggest a reassuring safety profile, though long-term use of melatonin may carry different considerations that travelers should be aware of. Still, melatonin is a hormone, not a simple herbal tea, and respect for its effects is warranted.

Common And Mild Side Effects

Side effects are usually short-lived and can resemble jet lag itself:

-

Daytime sleepiness or grogginess

-

Dizziness or a “heavy head” sensation

-

Headache

-

Nausea or reduced appetite

-

Vivid dreams or unusual sleep experiences

-

A “rocking” feeling, as if still on a boat

These are more likely with higher doses or poor timing (for example, taking melatonin in the middle of your biological day).

When To Avoid Melatonin Or Talk With A Clinician

Certain groups should avoid melatonin for jet lag, or use it only with medical guidance:

-

Pregnant or breastfeeding individuals – safety data are limited.

-

Children and adolescents – kids already have high natural melatonin levels, and long-term effects on development are not well understood.

-

People with epilepsy – some reports suggest melatonin may lower the seizure threshold.

-

People with migraines or serious psychiatric histories – melatonin can interact with these conditions.

-

Those with autoimmune disorders – due to melatonin’s immune effects.

-

Anyone taking interacting medications, including:

-

Warfarin or other vitamin K–antagonist blood thinners (possible increased bleeding risk)

-

Certain antidepressants, especially SSRIs

-

Other sedative sleep medications

-

Because supplements in the US are not regulated like prescription drugs, athletes subject to anti-doping rules should also be cautious; contamination with banned substances, while uncommon, is possible—and recent research examining melatonin for insomnia and cardiovascular health underscores the importance of consulting healthcare providers before extended use.

If you use melatonin—including formulations such as get to sleep:

-

Avoid alcohol the same evening.

-

Do not drive or operate machinery for several hours after taking it (ideally leave an eight-hour window).

-

Try your first dose at home on a non-work night, not for the first time on an airplane.

A conversation with your healthcare provider can help you weigh benefits and risks in your specific context.

Practical Travel Checklist: Pairing Melatonin For Jet Lag With Light And Habits

Melatonin for jet lag works best when it is part of a larger strategy. The strongest natural signal for your clock is still light, and your everyday habits can either support or work against your supplement.

Time Your Light Exposure

Use light and darkness to send the same message as your melatonin:

-

After eastward travel:

-

On the first day, avoid very bright light in the early morning.

-

Seek bright light in the mid- to late morning and early afternoon.

-

Dim lights in the evening and use blackout curtains or a sleep mask at night.

-

-

After westward travel:

-

Avoid bright morning light on arrival day.

-

Get sunlight in the late afternoon and early evening to help delay your clock.

-

As always, keep nights dark.

-

Simple tools help:

-

Dark sunglasses when you need to avoid light

-

A sleep mask for flights and hotel rooms

-

Blackout curtains or portable shades if your lodging is bright

"Light is the most powerful signal for the circadian system; melatonin is a helpful secondary cue." — Paraphrased from circadian rhythm research

Sleep, Food, Caffeine, And Naps

A few everyday choices can either support or disrupt your adjustment:

-

Sleep schedule: Move your bedtime and wake time toward destination time in the days before travel when possible. Even a one-hour shift can help.

-

Meals: Eat on the local schedule as soon as you can. Meals are secondary time cues for the clock.

-

Caffeine: Use it thoughtfully—morning coffee or tea can lift daytime fatigue, but avoid caffeine after midday so it does not compete with melatonin for jet lag at night.

-

Naps: Short “power naps” (20–30 minutes) can ease exhaustion. Long or late-afternoon naps, however, may delay your adjustment.

Example One-Week “Get To Sleep” Style Routine

Some travelers like a structured approach, similar to a “get to sleep 1‑week sample” routine:

-

Days −2 to 0 (before flight):

-

Gradually shift bedtime and wake time toward the destination by 30–60 minutes each day.

-

Increase morning light and reduce late-night screen time.

-

-

Days 1–3 (after arrival):

-

Take melatonin for jet lag 30–60 minutes before the new local bedtime.

-

Pair it with consistent wind-down habits: dim lights, quiet reading, or gentle stretching.

-

A product such as get to sleep can be folded into this plan as a short, intentional course.

-

-

Days 4–7:

-

Continue only if sleep is still misaligned; otherwise, step down and rely on light and routine.

-

The goal is not to stay on melatonin indefinitely, but to give your clock a clear, time-limited series of cues.

Future Directions In Melatonin For Jet Lag

Research into melatonin for jet lag is moving beyond simple pills toward more refined strategies.

New Delivery Methods

Scientists are exploring:

-

Nasal sprays that deliver melatonin rapidly into the bloodstream for travelers who need quick onset after late arrivals.

-

Carefully designed extended-release forms that maintain melatonin through the night without lingering into daytime, potentially supporting those who wake too early after long flights.

Personalized Timing And Dosing

Individual sensitivity to melatonin for jet lag varies. Current work is examining:

-

Biomarkers (such as timing of melatonin onset or clock genes) that could help predict each person’s ideal dose and timing.

-

Chronotherapy protocols that combine precisely timed melatonin with light exposure schedules to shorten recovery time.

-

Genetic studies that may explain why some travelers adjust in a day or two while others struggle for a week.

As the science of circadian biology deepens, the hope is to design more personalized, reliable guidance instead of one-size-fits-all rules.

Conclusion: Using Melatonin For Jet Lag With Intention

Melatonin for jet lag offers something many travelers quietly seek: a way to respect the body’s rhythms even while crossing the globe. Rather than forcing sleep, it provides a gentle, biologically familiar signal that night has come.

Used thoughtfully—at the right time, in a modest dose, and for a limited duration—melatonin can:

-

Shorten the time it takes to fall asleep in a new time zone

-

Improve sleep quality in the first nights after arrival

-

Reduce daytime fatigue, irritability, and mental fog

-

Help your internal clock settle into local time more quickly

The most reliable results appear when melatonin is paired with what we know from the science of circadian rhythms: timed light exposure, gradually adjusted sleep schedules, and simple travel habits that support recovery.

Short, deliberate courses of melatonin—often through well-designed products like get to sleep—can be part of a thoughtful routine for long-haul trips. The key is to treat melatonin for jet lag as a precise nudge to your internal clock, not a permanent crutch.

With that perspective, each long-haul trip becomes not only a change of place, but also a chance to better understand and care for the rhythms that carry you through every day and night.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.